“The population problem has no technical solution; it requires a fundamental extension on morality.” – Garret Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons”

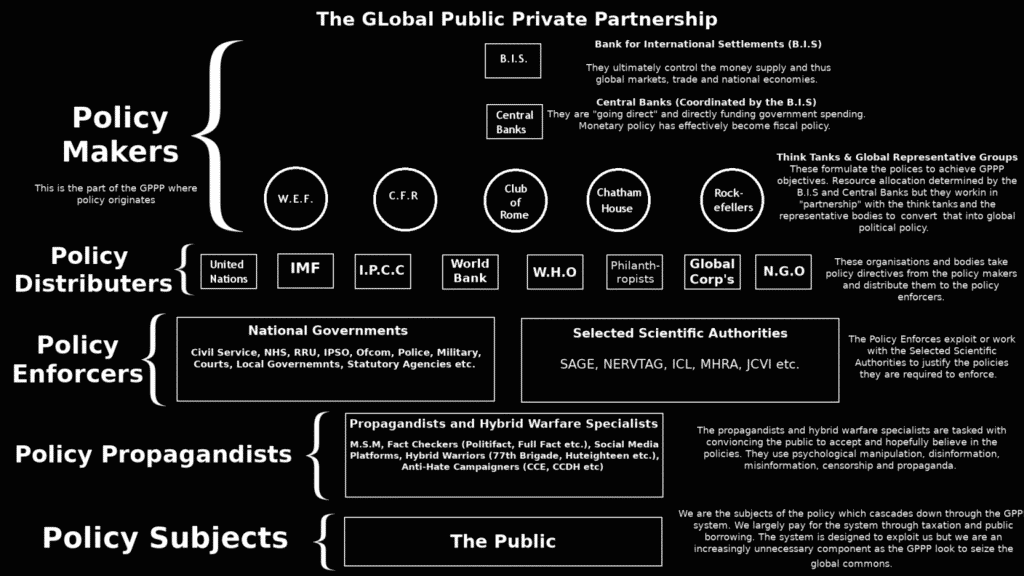

In Part 1 we explored the ongoing process of defining of the global commons and the claim of the stakeholder capitalists they they should be the “trustees” both of the commons and society. We are now going to look at how systems have been established to enable those stakeholders to seize them.

We should be mindful of what “global commons” means for the Global Public Private Partnership (GPPP). For them it means possession of everything: every resource on the planet, all land, all water, the air we breath and the natural world in its entirety, including all of us.

PRINCIPLES OF THE GLOBAL COMMONS

The notion of the “global commons” sprang from an amalgam of two principles in International Law. The Tragedy of The Commons (ToC) and the Common Heritage of Mankind (CHM).

In his 1968 paper on the ToC, the U.S. ecologist and eugenicist Garrett Hardin, building upon the earlier work of the 19th century economist William Forster Lloyd, outlined the population and resource problems as he saw them. He said “a finite world can support only a finite population; therefore, population growth must eventually equal zero.”

While logically this is ultimately true, if a whole raft of assumptions are accepted, the point at which zero population growth becomes necessary is unknown. The evidence suggests we are nowhere near that limit. Eugenicists, like Hardin, have claimed and continue to claim that the Earth faces a population problem. There is no evidence to support their view.

Hardin theorised that when a resource, such as land, is shared in “common,” people acting in rational self-interest will tend to increase their use of that resource because the cost is spread among all. He called this type of thinking a tragedy because, if all act accordingly, he maintained that the resource would dwindle to nothing and everyone suffer as a result.

Hardin insisted that this tragedy could not be averted. Therefore, as human beings were, in his eyes, incapable of grasping the bigger picture, the solutions were “managed” access to resources and “population control.”

While Hardin’s elitist ToC concept suggested regulated, enclosed (private) access to “common” resources, the Common Heritage of Mankind (CHM) rejected the idea of enclosure (privatisation). CHM instead advocated that a special group should be created by international treaty as “trustees” of the global commons. Seen as more “progressive,” it was no less elitist that Hardin’s concept.

The philosophical concept of CHM emerged onto the global political stage in the 1950’s but is was the 1967 speech by the Maltese ambassador to the U.N., Arvid Pardo, which established it as a principle of global governance. This eventually led to the 1982 U.N. Convention on Law of the Sea (LOSC).

Citing the CHM, in Article 137(2) of the LOSC, the U.N. declared:

“All rights in the resources of the Area are vested in mankind as a whole, on whose behalf the Authority shall act.”

That “Area”, in this case, was the the Earth’s oceans, including everything in and beneath them. The “authority” was defined in Section 4 as the International Seabed Authority (ISA). Article 137(2) of the LOSC is self contradictory.

The legal definition of “vested” implies that the whole of humanity, without exception, has an absolute right to access the global commons. In this instance, those commons were the oceans. While the legal definition speaks of ownership, “vested” seems to guarantee the no one can lay any individual claim to ownership of the oceans or its resources. Access is equally shared by all.

Supposedly, this alleged right can never be “defeated by a condition precedent.” This is repudiated entirely by “on whose behalf the Authority shall act.”

Who among the billions of Earth’s inhabitants gave the ISA this alleged authority? When were we asked if we wanted to cede our collective responsibility for the oceans to the ISA?

This authority was seized by U.N. diktat and nothing more. It is now the ISA who, by a condition precedent, control, limit and license our access to the oceans.

This is the essential deception at the heart of GPPP’s “global commons” paradigm. They sell their theft as stewardship of the resources vested in all humanity, while simultaneously seizing the entirety of those resources for themselves.

SEIZING THE GLOBAL COMMONS: THE OCEANS

When interpreted by International Law, the CHM appears to place the private ownership of the global commons, suggested by the ToC, beyond the reach of government stakeholder partners. They should have no more right to these riches than anyone else. Legal challenge to any claim should be a relatively straight forward process for any concerned individual or group minded to make one.

This is not even a remote possibility. International Law, as it pertains to the global commons, is a meaningless jumble of inconsistencies and contradictions that ultimately amounts to “might is right.” For anyone to challenge the GPPP’s claim they would need to retain a legal team capable of defeating the UN’s and a judiciary willing to find in their favour.

The “law” is ostensibly designed to leave us imagining that we have “protected” rights and responsibilities towards these shared resources. Whereas, if subjected to any reasonable scrutiny, the legal notion of the global commons looks more like a diversion to facilitate a robbery.

If we look at the ISA’s record of stakeholder engagement we quickly find their Strategic Plan for 2019 – 2020. This succinctly outlines how the scam operates:

In an ever-changing world, and in its role as custodian of the common heritage of mankind, ISA faces many challenges…The United Nations has adopted a new development agenda, entitled ‘Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.’[…] Of most relevance to ISA is SDG 14 — Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources.”

The shared resource – global commons – of the Earth’s oceans are not freely accessible to humanity as a whole anymore. Rather, the ISA determine who gets access to oceanic resources based upon Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Effectively they have turned access to the global commons into a new market.

The most vital questions we must ask is how these allocation decisions are made and by whom. This will reveal who controls these new highly regulated markets. The ISA state:

States parties, sponsoring States, flag States, coastal States, State enterprises, private investors, other users of the marine environment and interested global and regional intergovernmental organizations. All have a role in the development, implementation and enforcement of rules and standards for activities in the Area”

In addition, the ISA will:

“Strengthen cooperation and coordination with other relevant international organizations and stakeholders in order to…effectively safeguard the legitimate interests of members of ISA and contractors…The rules, regulations and procedures governing mineral exploitation…are underpinned by sound commercial principles in order to promote investment…taking into account trends and developments relating to deep seabed mining activities, including objective analysis of world metal market conditions and metal prices, trends and prospects…based on consensus…that allows for stakeholder input in appropriate ways.”

The Global Public Private Partnership (GPPP) of governments, global corporations (other users of the marine environment), their major shareholders (private investors) and philanthropic foundations (private investors) are the stakeholders. They, not us, will have an input to ensure the rules, regulations and procedures will promote investment that will safeguard their interests.

In the space of a few short decades, broad concepts have evolved into principles of International Law which have subsequently been applied to create a regulatory framework for controlled access to the all the resources in the oceans. What was once genuinely a global resource is now the sole province of the GPPP and its network of stakeholder capitalists.

THE GLOBAL COMMONS ARE GLOBAL

We should be wary of falling into the trap of thinking the GPPP comprises solely of the western hegemony. The stories we are fed about the global confrontation between superpowers are often superficial.

While there are undoubtedly tensions within the GPPP, as each player jostles for a bigger slice of the new markets, the GPPP network itself is a truly global collaboration. This doesn’t mean that conflict between nation states is impossible but, as ever, any such conflict will be fought for a reason absent from the official explanation.

SDG’s led to net zero policies and they stipulate, among a swath of enforced changes, the end of petrol and diesel transport. We are all under orders to switch to electric vehicles (EVs) which the vast majority won’t be able to afford. In turn, this means a massive increase in demand for lithium-ion batteries.

Manufacturing these will require a lot more cobalt which is widely considered to be the most critical supply chain risk for producing EVs. The World Bank estimate that the growth in demand for cobalt between 2018 and 2050 will be somewhere in the region of 450%. To say this is a “market opportunity” is a massive understatement.

The ISA have granted 5 cobalt exploration contracts to JOGMEC (Japan), COMRA (China), Russia, the Republic of Korea and CPRM (Brazil). When located deposits become commercially viable, as they undoubtedly will, the corporate feeding frenzy can begin.

Corporations, such as the weapons manufacturer Lockheed Martin, with its wholly owned subsidiary UK Seabed Resources (UKSR), are also among the many ISA stakeholders. UKSR received their exploration license for the South Pacific in 2013. As an ISA exploration contractor, UKSR stakeholders are free to submit their recommendations for amendments to the ISA regulations governing their own mining operations.